I groaned when I discovered that I had drawn the 8:30 a.m. Saturday keynote slot at a major spirituality congress last October because I know what audiences are like at that time of the weekend: zombies. It takes them a full hour to come to life. That being the amount of time allotted to me, I decided to rouse them with this prayer by Dean Alan Jones which I found by browsing the Internet:

I groaned when I discovered that I had drawn the 8:30 a.m. Saturday keynote slot at a major spirituality congress last October because I know what audiences are like at that time of the weekend: zombies. It takes them a full hour to come to life. That being the amount of time allotted to me, I decided to rouse them with this prayer by Dean Alan Jones which I found by browsing the Internet:

"I want to thank you, Lord, for being close to me. So far this day, with your help, I haven't been impatient, lost my temper, been grumpy, judgmental or envious of anyone. But I will be getting out of bed in a minute and I think I will really need your help then. Amen."

"I want to thank you, Lord, for being close to me. So far this day, with your help, I haven't been impatient, lost my temper, been grumpy, judgmental or envious of anyone. But I will be getting out of bed in a minute and I think I will really need your help then. Amen."

As I hoped, the audience responded with laughter and began to perk up. At the end of my presentation, however, two women stopped to tell me they enjoyed my talk but felt the prayer was inappropriate. Puzzled, I asked them why.

As I hoped, the audience responded with laughter and began to perk up. At the end of my presentation, however, two women stopped to tell me they enjoyed my talk but felt the prayer was inappropriate. Puzzled, I asked them why.

"It seemed disrespectful," one said, "like you were making fun of God."

"It seemed disrespectful," one said, "like you were making fun of God."

The other nodded and said, "We come to a day like this for spiritual reasons, not entertainment."

The other nodded and said, "We come to a day like this for spiritual reasons, not entertainment."

*****

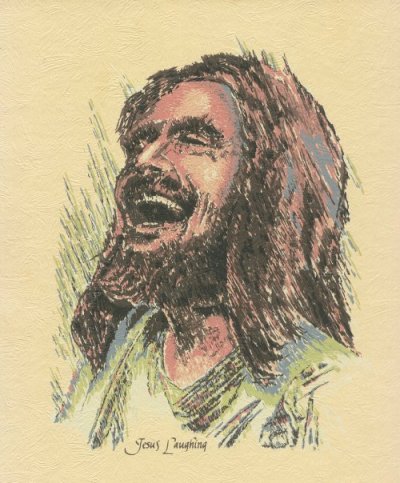

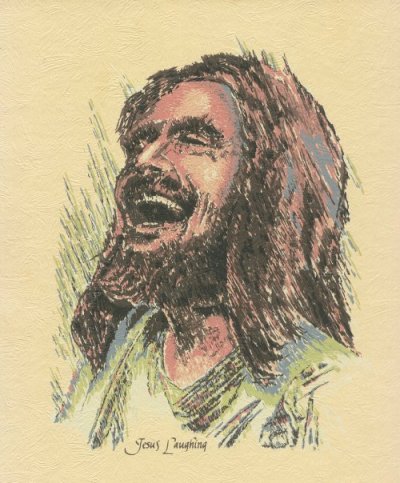

By now I should have anticipated a refusal to accept the gift of laughter from some who gather at Catholic conferences. We find them everywhere in our world and in our Church. Such persons are uncomfortable with lightness and humor, especially when associated with religion. They feel irreverent if they chuckle in church, hear a joke about Jesus playing golf or read stories about saints like Francis who called himself a fool for Christ. To them religion is deadly serious. They feel threatened by those who do not subscribe to a sacred-is-grim philosophy.

By now I should have anticipated a refusal to accept the gift of laughter from some who gather at Catholic conferences. We find them everywhere in our world and in our Church. Such persons are uncomfortable with lightness and humor, especially when associated with religion. They feel irreverent if they chuckle in church, hear a joke about Jesus playing golf or read stories about saints like Francis who called himself a fool for Christ. To them religion is deadly serious. They feel threatened by those who do not subscribe to a sacred-is-grim philosophy.

I suspect we've always had these unfortunates, but I am concerned that they seem to be on the increase in our Church. As we polarize more in our definition of what's proper and improper in spreading the Good News, our sense of humor diminishes. We laugh at ourselves less and wring our hands more. Our spirits sink and we become witnesses to the converse of the Good News. Then we wonder why our young are not attracted to our faith.

I suspect we've always had these unfortunates, but I am concerned that they seem to be on the increase in our Church. As we polarize more in our definition of what's proper and improper in spreading the Good News, our sense of humor diminishes. We laugh at ourselves less and wring our hands more. Our spirits sink and we become witnesses to the converse of the Good News. Then we wonder why our young are not attracted to our faith.

If we are fearful, dispirited and constantly bewailing the state of our Church, world and morality, that's the mirror of Christ we reflect. We teach a thousandfold more by who we are than what we know, say or do.

If we are fearful, dispirited and constantly bewailing the state of our Church, world and morality, that's the mirror of Christ we reflect. We teach a thousandfold more by who we are than what we know, say or do.

St. Francis knew this well. The story is told that he gathered some followers to go preach in the town. They walked from one end to the other without saying a word, then Francis told them they had preached. He obviously found example more important than words.

St. Francis knew this well. The story is told that he gathered some followers to go preach in the town. They walked from one end to the other without saying a word, then Francis told them they had preached. He obviously found example more important than words.

We know from psychotherapy that, when an individual suffers from depression, humor is one of the first gifts to go. A depressed person no longer laughs. The same holds true for families and institutions. In recent years, Catholic leaders and laity alike have noted an increase in the classic symptoms of depression among our People of God: cynicism, criticizing, blaming, complaining, resenting, rejecting, paranoia, anger, withdrawal, skepticism, distrust, despair, derision and loss of humor, especially the ability to take ourselves lightly.

We know from psychotherapy that, when an individual suffers from depression, humor is one of the first gifts to go. A depressed person no longer laughs. The same holds true for families and institutions. In recent years, Catholic leaders and laity alike have noted an increase in the classic symptoms of depression among our People of God: cynicism, criticizing, blaming, complaining, resenting, rejecting, paranoia, anger, withdrawal, skepticism, distrust, despair, derision and loss of humor, especially the ability to take ourselves lightly.

I can attest to this loss. When I began writing my weekly column in 1967, humor was widespread and treasured in the Catholic press. Readers loved an occasional column on our foibles and inconsistencies. For example, at a time in history when priests first began leaving the priesthood in numbers, one widely reprinted quip mimicked the card we all carried in our wallets which read, "I am a Catholic. In case of accident, call a priest." The revised satirical card read, "I am an ex-Catholic. In case of an accident, call an ex-priest."

I can attest to this loss. When I began writing my weekly column in 1967, humor was widespread and treasured in the Catholic press. Readers loved an occasional column on our foibles and inconsistencies. For example, at a time in history when priests first began leaving the priesthood in numbers, one widely reprinted quip mimicked the card we all carried in our wallets which read, "I am a Catholic. In case of accident, call a priest." The revised satirical card read, "I am an ex-Catholic. In case of an accident, call an ex-priest."

Today such humor is rare. Whole issues of diocesan papers are published without a single smile and, if I put one in my column, I can be sure to hear from a few readers who charge me with irreverence. I sigh and imagine God rolling beautiful blue eyes and saying, "Lighten up."

Today such humor is rare. Whole issues of diocesan papers are published without a single smile and, if I put one in my column, I can be sure to hear from a few readers who charge me with irreverence. I sigh and imagine God rolling beautiful blue eyes and saying, "Lighten up."

*****

How did we get so glum? When did we start devaluing those other gifts of the Spirit: play, humor, hope, idealism and joy? We have a rich heritage acclaiming humor as a gift but so bereft are we today that an ecumenical group called The Fellowship of Merry Christians is now dedicated to preserving humor, joy and lightness in our faith. Their mission statement reads: "Our modest aim is to recapture the spirit of joy, humor, unity and healing power of the early Christians. We try to be merry more than twice a year." Itís wise to note that preservation organizations come into existence only when there's danger of losing a treasure.

How did we get so glum? When did we start devaluing those other gifts of the Spirit: play, humor, hope, idealism and joy? We have a rich heritage acclaiming humor as a gift but so bereft are we today that an ecumenical group called The Fellowship of Merry Christians is now dedicated to preserving humor, joy and lightness in our faith. Their mission statement reads: "Our modest aim is to recapture the spirit of joy, humor, unity and healing power of the early Christians. We try to be merry more than twice a year." Itís wise to note that preservation organizations come into existence only when there's danger of losing a treasure.

The Jewish Talmud holds, "We will be held accountable for neglecting to enjoy the legitimate pleasures the Lord sends us." I thought of these words when my husband and I witnessed a breathtaking rainbow in Ireland last year, one that began on one side of the mountain, spanned the bay and ended in brilliance on the other side. The following day while visiting with Condy, an old bachelor who frequented our rented cottage, I asked him if he saw the rainbow and he nodded unenthusiastically. Like Jeremiah, I can't shut up when confronted with the glory of God. So I added, "It was the most beautiful rainbow I've ever seen anywhere," hoping he would agree.

The Jewish Talmud holds, "We will be held accountable for neglecting to enjoy the legitimate pleasures the Lord sends us." I thought of these words when my husband and I witnessed a breathtaking rainbow in Ireland last year, one that began on one side of the mountain, spanned the bay and ended in brilliance on the other side. The following day while visiting with Condy, an old bachelor who frequented our rented cottage, I asked him if he saw the rainbow and he nodded unenthusiastically. Like Jeremiah, I can't shut up when confronted with the glory of God. So I added, "It was the most beautiful rainbow I've ever seen anywhere," hoping he would agree.

Condy paused for a long moment and then said, "Aye, but there are some who say that if a rainbow starts on one side of the bay and ends on the other, bad luck is coming." Then I did shut up. But I wonder how God feels when he gifts us with something of beauty to lift our spirits only to find us rejecting it in fear of having to pay for it later.

Condy paused for a long moment and then said, "Aye, but there are some who say that if a rainbow starts on one side of the bay and ends on the other, bad luck is coming." Then I did shut up. But I wonder how God feels when he gifts us with something of beauty to lift our spirits only to find us rejecting it in fear of having to pay for it later.

Souls like Condy's flourish everywhere. Some are even organized into groups such as the one devoted to finding the single flaw in the medieval tapestries covering the walls of castles in Europe. It seems that orders of nuns spent a lifetime creating these works of art but, in order to profess humbly that only God is perfect, they deliberately inserted a mistake in each piece of work. I was astounded to learn that this flaw-detecting group charters flights to Europe where members spend days poring over a single tapestry to spot the mistake.

Souls like Condy's flourish everywhere. Some are even organized into groups such as the one devoted to finding the single flaw in the medieval tapestries covering the walls of castles in Europe. It seems that orders of nuns spent a lifetime creating these works of art but, in order to profess humbly that only God is perfect, they deliberately inserted a mistake in each piece of work. I was astounded to learn that this flaw-detecting group charters flights to Europe where members spend days poring over a single tapestry to spot the mistake.

I believe they provide an apt metaphor for those in our Church today who are so vigilantly searching for flaws that they sacrifice joy on the altar of righteousness. Richard Rohr, O.F.M., says, "If you've lost the joy, you've lost, no matter how just the cause is. A bitter revolutionary becomes a victim of that he is fighting." Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., would have agreed. He penned the simple truth, "We follow those who offer the most hope" not fear, not despair, not depression, but hope. People do not embrace a faith and come to church to get depressed but to get hope, to share the Spirit and to be around people of hope, idealism and joy.

I believe they provide an apt metaphor for those in our Church today who are so vigilantly searching for flaws that they sacrifice joy on the altar of righteousness. Richard Rohr, O.F.M., says, "If you've lost the joy, you've lost, no matter how just the cause is. A bitter revolutionary becomes a victim of that he is fighting." Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., would have agreed. He penned the simple truth, "We follow those who offer the most hope" not fear, not despair, not depression, but hope. People do not embrace a faith and come to church to get depressed but to get hope, to share the Spirit and to be around people of hope, idealism and joy.

*****

Humor has been called a recess for the spirit and laughter a little like changing a baby's diaper. You know it won't change anything permanently but it will make everything O.K. for a while. Humor offers multiple gifts. It gives us a sense of perspective. For example, how could I feel self-important after a woman told me she was reading my column for Lent?

Humor has been called a recess for the spirit and laughter a little like changing a baby's diaper. You know it won't change anything permanently but it will make everything O.K. for a while. Humor offers multiple gifts. It gives us a sense of perspective. For example, how could I feel self-important after a woman told me she was reading my column for Lent?

We can get so overly concerned about trivialities in our daily lives that only later do we recognize the absurd importance we granted them at the time. We shake our heads and wonder why we didn't laugh at them instead of allowing them to disturb our serenity. Humor invites us to examine life in an unconventional, offbeat and delightful way, as children do. A grandmother in one of my workshops shared that when she was feeding lunch to her grandchildren, one said in distress, "Grandma, we forgot to pray. We always pray at our other grandma's."

We can get so overly concerned about trivialities in our daily lives that only later do we recognize the absurd importance we granted them at the time. We shake our heads and wonder why we didn't laugh at them instead of allowing them to disturb our serenity. Humor invites us to examine life in an unconventional, offbeat and delightful way, as children do. A grandmother in one of my workshops shared that when she was feeding lunch to her grandchildren, one said in distress, "Grandma, we forgot to pray. We always pray at our other grandma's."

His older sister shushed him, saying, "Jeffrey, we don't have to pray here. This grandma's food is always good."

His older sister shushed him, saying, "Jeffrey, we don't have to pray here. This grandma's food is always good."

*****

Humor instills in us a sense of joy. Watching a baby discover her feet for the first time or hearing a youngster describe the monster in his closet leads our bones to laughter and our souls to joy. Reinhold Niebuhr asserted, "Humor is prelude to faith and laughter is the beginning of prayer." How contrary these words are to sacred-is-grim adherents! Sadly, they would be likely to reject them simply because they have so little experience of joy in the ordinary which erupts into spontaneous prayer.

Humor instills in us a sense of joy. Watching a baby discover her feet for the first time or hearing a youngster describe the monster in his closet leads our bones to laughter and our souls to joy. Reinhold Niebuhr asserted, "Humor is prelude to faith and laughter is the beginning of prayer." How contrary these words are to sacred-is-grim adherents! Sadly, they would be likely to reject them simply because they have so little experience of joy in the ordinary which erupts into spontaneous prayer.

Humor gives us an opportunity to acknowledge our shortcomings, as the obese comedian did when he introduced himself as a recovering anorexic. We all have shortcomings, but we spend most of our lives trying to conceal them. Often, humor allows us to admit to them publicly, to acknowledge that we aren't perfect. Humor, after all, springs from the same root as humility, human and humus: earthiness.

Humor gives us an opportunity to acknowledge our shortcomings, as the obese comedian did when he introduced himself as a recovering anorexic. We all have shortcomings, but we spend most of our lives trying to conceal them. Often, humor allows us to admit to them publicly, to acknowledge that we aren't perfect. Humor, after all, springs from the same root as humility, human and humus: earthiness.

It's difficult to remain poised and sophisticated when one forgets her spouse's name while introducing him to a large group of her colleagues as in a recent situation I experienced. Unable to laugh at herself, this woman became so embarrassed she left the gathering. Instead of putting us at ease by joining together in laughter over a common shortcoming when one is introducing many to many, she spoiled the party.

It's difficult to remain poised and sophisticated when one forgets her spouse's name while introducing him to a large group of her colleagues as in a recent situation I experienced. Unable to laugh at herself, this woman became so embarrassed she left the gathering. Instead of putting us at ease by joining together in laughter over a common shortcoming when one is introducing many to many, she spoiled the party.

Humor allows us to see the bright side of life, even when things look dark. I have one son who is a master at this, saying, "But think of it this way..." and coming up with outrageous positives in negative situations. Good-news/bad-news jokes serve the same purpose. A friend of mine said she knew she was a writer the day her pressure cooker exploded and, scanning the tomatoes dripping from the ceiling, she thought, "This will make a great article."

Humor allows us to see the bright side of life, even when things look dark. I have one son who is a master at this, saying, "But think of it this way..." and coming up with outrageous positives in negative situations. Good-news/bad-news jokes serve the same purpose. A friend of mine said she knew she was a writer the day her pressure cooker exploded and, scanning the tomatoes dripping from the ceiling, she thought, "This will make a great article."

Humor invites us to recognize the absurdities in life and in our Church. Yes, there are absurdities in our Church and it's O.K. to enjoy them as long as we admit our part in them, recognizing that we are the Church. The priest who was so frustrated over the failure of some in the pew to extend their hand at the sign of peace that he threatened to set up Sign of Peace and No Sign of Peace sections surfaced an absurdity to make a point.

Humor invites us to recognize the absurdities in life and in our Church. Yes, there are absurdities in our Church and it's O.K. to enjoy them as long as we admit our part in them, recognizing that we are the Church. The priest who was so frustrated over the failure of some in the pew to extend their hand at the sign of peace that he threatened to set up Sign of Peace and No Sign of Peace sections surfaced an absurdity to make a point.

We invite priests to serve if they were married ministers in another religion before they became Catholic and were ordained, yet disallow marriage for those who are Catholic, leading some satirists to advise young Catholics called to both the priesthood and marriage to become ordained first as Episcopal priests and then seek admission to serve in our Church. Absurdities like these abound. We can surface and enjoy them or let them drive us away in anger. Jesus exposed absurdity when he instructed, "Let the one among you without sin cast the first stone."

We invite priests to serve if they were married ministers in another religion before they became Catholic and were ordained, yet disallow marriage for those who are Catholic, leading some satirists to advise young Catholics called to both the priesthood and marriage to become ordained first as Episcopal priests and then seek admission to serve in our Church. Absurdities like these abound. We can surface and enjoy them or let them drive us away in anger. Jesus exposed absurdity when he instructed, "Let the one among you without sin cast the first stone."

Humor and creativity utilize the same brain processes. Those in the creative arts know that, when the spirit suffers, so does creativity. In recent years, companies in search of solutions to baffling problems or in the business of developing new products frequently begin their 'think tank' sessions with a game of some sort because it opens up the creative side of engineers' brains.

Humor and creativity utilize the same brain processes. Those in the creative arts know that, when the spirit suffers, so does creativity. In recent years, companies in search of solutions to baffling problems or in the business of developing new products frequently begin their 'think tank' sessions with a game of some sort because it opens up the creative side of engineers' brains.

I attended a workshop where family religious educator Dr. Kathleen Chesto used this technique to free some 100 religious educators from agendas weighing them down on arrival. She set up groups of 10 to a table containing pieces of a jigsaw puzzle and asked us to compete with the other tables in finishing first. She neglected to inform us that she had removed the picture and a few pieces. As we struggled to put the puzzle together without any idea of the big picture -much as we do in religious education- and then realized there were missing pieces, our frustration and laughter both increased.

I attended a workshop where family religious educator Dr. Kathleen Chesto used this technique to free some 100 religious educators from agendas weighing them down on arrival. She set up groups of 10 to a table containing pieces of a jigsaw puzzle and asked us to compete with the other tables in finishing first. She neglected to inform us that she had removed the picture and a few pieces. As we struggled to put the puzzle together without any idea of the big picture -much as we do in religious education- and then realized there were missing pieces, our frustration and laughter both increased.

By the time we sat down to listen to Dr. Chesto, we were in community and our spirits were light and open to her words. Perhaps we need to start a few parish council meetings with a jigsaw-puzzle competition.

By the time we sat down to listen to Dr. Chesto, we were in community and our spirits were light and open to her words. Perhaps we need to start a few parish council meetings with a jigsaw-puzzle competition.

*****

But back to the question: How did we become so glum and worry-laden in the first place? We live today in a culture of negativity, a culture that emerged in the world community somewhere in the 60ís and seeped into the Church. It's almost culturally unacceptable to be upbeat today and those who are openly hopeful are labeled naive idealists. With media and press obsessed with scandal, controversy and crime, while deliberately ignoring positives like reconciliations, communal humanitarianism and ordinary kindliness, it's easy to fall into the trap of cultural negativism.

But back to the question: How did we become so glum and worry-laden in the first place? We live today in a culture of negativity, a culture that emerged in the world community somewhere in the 60ís and seeped into the Church. It's almost culturally unacceptable to be upbeat today and those who are openly hopeful are labeled naive idealists. With media and press obsessed with scandal, controversy and crime, while deliberately ignoring positives like reconciliations, communal humanitarianism and ordinary kindliness, it's easy to fall into the trap of cultural negativism.

Many an oldster has pointed out that people had more hope during the Depression and World War II years than today, times of economic health and peace. Their anecdotal observations are supported by studies indicating that, in this century, the level of contentment and satisfaction in America peaked in the 1950's and has eroded each decade since, in spite of a higher standard of living for the middle and upper economic classes, medical breakthroughs and increased individual rights. It's our perception of the world that's faulty, not the world itself.

Many an oldster has pointed out that people had more hope during the Depression and World War II years than today, times of economic health and peace. Their anecdotal observations are supported by studies indicating that, in this century, the level of contentment and satisfaction in America peaked in the 1950's and has eroded each decade since, in spite of a higher standard of living for the middle and upper economic classes, medical breakthroughs and increased individual rights. It's our perception of the world that's faulty, not the world itself.

We move from realism to negativity when negative attitudes and behaviors become predominant in our lives. We look first to what's wrong rather than right, for the flaws in the tapestry of life. Our initial reaction to a given situation is, "It wonít work" or "Thereís something fishy about it" or, in the case of beautiful weather, "It wonít last." We point out that Babe Ruth struck out 1,330 times.

We move from realism to negativity when negative attitudes and behaviors become predominant in our lives. We look first to what's wrong rather than right, for the flaws in the tapestry of life. Our initial reaction to a given situation is, "It wonít work" or "Thereís something fishy about it" or, in the case of beautiful weather, "It wonít last." We point out that Babe Ruth struck out 1,330 times.

We have several wonderful words for those who are chronically negative: begrudgers, curmudgeons, grumps and negaholics. The character Weeser, played by Shirley MacLaine in the movie Steel Magnolias, serves as a fine example of a negaholic. When accused of being a grump, she retorted, "I am not a grump. Iíve just been in a bad mood the last 40 years."

We have several wonderful words for those who are chronically negative: begrudgers, curmudgeons, grumps and negaholics. The character Weeser, played by Shirley MacLaine in the movie Steel Magnolias, serves as a fine example of a negaholic. When accused of being a grump, she retorted, "I am not a grump. Iíve just been in a bad mood the last 40 years."

Those who live with grumps know how depressing they can be to the spirit. One woman told me that, when she opened her drapes one snowy morning and saw a neighbor shoveling her walks, her spirits soared in gratitude and she thanked God for kindness in the form of good neighbors. But when she called her husband's attention to the act and he grunted suspiciously, "Wonder what he wants," her good spirits evaporated and she was depressed all morning. It was not because she suspected her neighbor of ulterior motives but because she lived with a man who personified H. L. Menckenís definition of a Puritan: One who has a haunting fear that someone somewhere might be happy.

Those who live with grumps know how depressing they can be to the spirit. One woman told me that, when she opened her drapes one snowy morning and saw a neighbor shoveling her walks, her spirits soared in gratitude and she thanked God for kindness in the form of good neighbors. But when she called her husband's attention to the act and he grunted suspiciously, "Wonder what he wants," her good spirits evaporated and she was depressed all morning. It was not because she suspected her neighbor of ulterior motives but because she lived with a man who personified H. L. Menckenís definition of a Puritan: One who has a haunting fear that someone somewhere might be happy.

The good news is that negativity is a learned reflex and anything that can be learned can also be unlearned. Babies aren't born negative. Teachers are quick to recognize children who come from negative families. Their first reaction to anything new is, "I can't do it," "It's too hard" or "It's not worth the effort." They sacrifice the joy of anticipation, challenge and mastery by hugging their negativism.

The good news is that negativity is a learned reflex and anything that can be learned can also be unlearned. Babies aren't born negative. Teachers are quick to recognize children who come from negative families. Their first reaction to anything new is, "I can't do it," "It's too hard" or "It's not worth the effort." They sacrifice the joy of anticipation, challenge and mastery by hugging their negativism.

The bad news is that bad feelings drive out good feelings. Psychologists call this 'emotional displacement.' You can't be happy and angry at the same time. How often do we find ourselves in a group where good feelings prevail only to have a negaholic enter the group and turn it sour, maybe even angry?

The bad news is that bad feelings drive out good feelings. Psychologists call this 'emotional displacement.' You can't be happy and angry at the same time. How often do we find ourselves in a group where good feelings prevail only to have a negaholic enter the group and turn it sour, maybe even angry?

Rabbi Edwin Friedman calls these people pathogens and points out that while they exist in all churches, a few can infect many and produce a sick parish. As both a psychotherapist and rabbi, Dr. Friedman works with sick parishes of many denominations. He has discovered that more than new leadership is required to return a parish to health. The pathology has to be treated. In other words, we have to heal ourselves first.

Rabbi Edwin Friedman calls these people pathogens and points out that while they exist in all churches, a few can infect many and produce a sick parish. As both a psychotherapist and rabbi, Dr. Friedman works with sick parishes of many denominations. He has discovered that more than new leadership is required to return a parish to health. The pathology has to be treated. In other words, we have to heal ourselves first.

Merely voicing positivity is self-delusion, like running around telling people to be happy in an earthquake. The healthiest position in all of life is hopeful realism: Yes, we've got problems, but where's the hope here? To heal sick parishes, dioceses and, indeed, the world Church, we must exercise reverse emotional displacement, allowing good feelings to drive out bad feelings.

Merely voicing positivity is self-delusion, like running around telling people to be happy in an earthquake. The healthiest position in all of life is hopeful realism: Yes, we've got problems, but where's the hope here? To heal sick parishes, dioceses and, indeed, the world Church, we must exercise reverse emotional displacement, allowing good feelings to drive out bad feelings.

Admitting to the sickness publicly is but the first step. Successful treatment requires medication in the form of prayer, repentance, forgiveness and a change of heart. A comedian quipped that most of today's vocal Christians look as if they'd been baptized in vinegar, and a Catholic pastor said, "Sometimes when I'm celebrating Mass, I feel as if I am the only one celebrating."

Admitting to the sickness publicly is but the first step. Successful treatment requires medication in the form of prayer, repentance, forgiveness and a change of heart. A comedian quipped that most of today's vocal Christians look as if they'd been baptized in vinegar, and a Catholic pastor said, "Sometimes when I'm celebrating Mass, I feel as if I am the only one celebrating."

If we become a people of hope and joy again, our Church will echo the same message. When we talk about nurturing vocations, we may be focusing on the wrong end. We're nurturing the altar when we should be nurturing the pew. If the pew is welcoming, joyous and alive, we'll draw vocations. We follow those who offer the most hope, remember? But when we're constantly looking for that flaw in the tapestry on the altar instead of in the pew, we'll find it.

If we become a people of hope and joy again, our Church will echo the same message. When we talk about nurturing vocations, we may be focusing on the wrong end. We're nurturing the altar when we should be nurturing the pew. If the pew is welcoming, joyous and alive, we'll draw vocations. We follow those who offer the most hope, remember? But when we're constantly looking for that flaw in the tapestry on the altar instead of in the pew, we'll find it.

But just as depression is contagious, so is positivity. When we open our spirits again to joy, hope, play, humor and idealism, perceiving them as invaluable gifts of the Spirit, our faith communities will become transformed. As we lighten up, the flaws in the tapestry we call Church will remain but we won't notice them.

But just as depression is contagious, so is positivity. When we open our spirits again to joy, hope, play, humor and idealism, perceiving them as invaluable gifts of the Spirit, our faith communities will become transformed. As we lighten up, the flaws in the tapestry we call Church will remain but we won't notice them.

*****

I began with a prayer and I end with a lighthearted poem, attributed to Hilaire Belloc, a Catholic author with a hearty sense of humor:

I began with a prayer and I end with a lighthearted poem, attributed to Hilaire Belloc, a Catholic author with a hearty sense of humor:

Wherever the Catholic sun doth shine,

Wherever the Catholic sun doth shine,

there's music and laughter and good red wine.

there's music and laughter and good red wine.

At least I've heard them tell it so.

At least I've heard them tell it so.

Benedicamos Domino.

Benedicamos Domino.

Through the grace of God and a bit of hard work, we can -and indeed we must- recapture the treasure we once displayed for all the world to see!

Through the grace of God and a bit of hard work, we can -and indeed we must- recapture the treasure we once displayed for all the world to see!

Dolores Curran

Dolores Curran

(Described in a 1991 St. Anthony Messenger profile as a writer, lecturer, wife, mother, educator, family counselor, pro-life feminist and optimist

'with the insight of Ann Landers and the wit of Erma Bombeck.' Her weekly syndicated column, "Talks With Parents," reaches four million readers. Her books include Working With Parents (American Guidance Service), Stress and the Healthy Family (English and Spanish editions, HarperSanFrancisco) and Traits of a Healthy Family (HarperSanFrancisco). This year, Twenty-Third Publications has published the revised Dolores Curran on Family Prayer.)

St. Anthony Messenger/ Back Issues/ July 1997

Back to Apprentice Weavers

|