CREATION OF A MANDALA

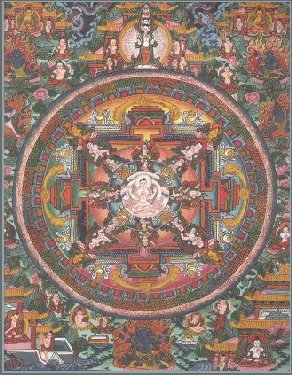

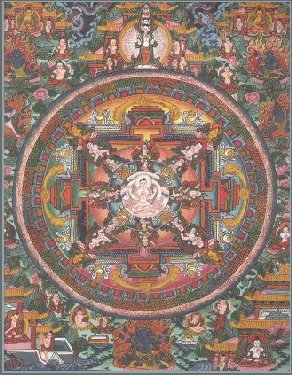

The origin of the mandala is the center, a dot. It is a symbol

apparently free of dimensions. It means a 'seed', 'sperm', 'drop', the salient

starting point. It is the gathering center in which the outside energies are

drawn, and in the act of drawing the forces, the devotee's own energies

unfold and are also drawn. Thus it represents the outer and inner spaces. Its

purpose is to remove the object-subject dichotomy. In the process, the

mandala is consecrated to a deity.

In its creation, a line materializes out of a dot. Other lines are

drawn until they intersect, creating triangular geometrical patterns. The

circle drawn around stands for the dynamic consciousness of the initiated.

The outlying square symbolizes the physical world bound in four

directions, represented by the four gates; and the midmost or central area is the

residence of the deity. Thus the center is visualized as the essence

and the circumference as grasping, thus in its complete picture a mandala

means grasping the essence.

CONSTRUCTION OF A MANDALA

Before a monk is permitted to work on constructing a mandala he must

undergo a long period of technical artistic training and memorization,

learning how to draw all the various symbols and studying related philosophical

concepts. At the Namgyal monastery (the personal monastery of the Dalai lama),

for example, this period is three years.

In the early stages of painting, the monks sit on the outer part of

the unpainted mandala base, always facing the center. For larger sized

Mandalas, when the mandala is about halfway completed, the monks then stand on

the floor, bending forward to apply the colors.

Traditionally, the mandala is divided into four quadrants and one

monk is assigned to each. At the point where the monks stand to apply the

colors, an assistant joins each of the four. Working co-operatively, the

assistants help by filling in areas of color while the primary four monks

outline the other details.

The monks memorize each detail of the mandala as part of their

monastery's training program. It is important to note that the mandala is

explicitly based on the Scriptural texts. At the end of each work session, the

monks dedicate any artistic or spiritual merit accumulated from this

activity to the benefit of others. This practice prevails in the execution of all

ritual arts.

There is good reason for the extreme degree of care and attention

that the monks put into their work: they are actually imparting the Buddha's

teachings. Since the mandala contains instructions by the Buddha for

attaining enlightenment, the purity of their motivation and the

perfection of their work allows viewers the maximum benefit.

Each detail in all four quadrants of the mandala faces the center, so

that it is facing the resident deity of the mandala. Thus, from the

perspective of both the monks and the viewers standing around the mandala, the

details in the quadrant closest to the viewer appear upside down, while those

in the most distant quadrant appear right side up.

Generally, each monk keeps to his quadrant while painting the square

palace. When they are painting the concentric circles, they work in tandem,

moving all around the mandala. They wait until an entire cyclic phase or

layer is completed before moving outward together. This ensures that balance is

maintained, and that no quadrant of the mandala grows faster than another.

The preparation of a mandala is an artistic endeavor, but at the same

time it is an act of worship. In this form of worship concepts and form are

created in which the deepest intuitions are crystallized and expressed as

spiritual art. The design, which is usually meditated upon, is a continuum

of spatial experiences, the essence of which precedes its existence,

which means that the concept precedes the form.

In its most common form, the mandala appears as a series of concentric

circles. Each mandala has its own resident deity housed in the square

structure situated concentrically within these circles. Its perfect

square shape indicates that the absolute space of wisdom is without

aberration.

This square structure has four elaborate gates. These four doors

symbolize the bringing together of the four boundless thoughts namely - loving

kindness, compassion, sympathy, and equanimity. Each of these

gateways is adorned with bells, garlands and other decorative items. This square

form defines the architecture of the mandala described as a four-sided

palace or temple. A palace because it is the residence of the presiding deity

of the mandala, a temple because it contains the essence of the Buddha.

The series of circles surrounding the central palace follow an intense

symbolic structure. Beginning with the outer circles, one often finds

a ring of fire, frequently depicted as a stylized scrollwork. This

symbolizes the process of transformation which ordinary human beings have to undergo

before entering the sacred territory within. This is followed by a ring of

thunderbolt or diamond scepters (vajra), indicating the

indestructibility and diamond like brilliance of the mandala's spiritual realms.

In the next concentric circle, particularly those mandalas which

feature wrathful deities, one finds eight cremation grounds arranged in a

wide band. These represent the eight aggregates of human consciousness which tie

man to the phenomenal world and to the cycle of birth and rebirth.

Finally, at the center of the mandala lies the deity, with whom the

mandala is identified. It is the power of this deity that the mandala is said

to be invested with. Most generally the central deity may be one of the

following three:

1) Peaceful Deities: A peaceful deity symbolizes its own particular

existential and spiritual approach. For example, the image of

Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara symbolizes compassion as the central focus of the

spiritual experience; that of Manjushri takes wisdom as the central focus; and

that of Vajrapani emphasizes the need for courage and strength in the quest

for sacred knowledge.

1) Peaceful Deities: A peaceful deity symbolizes its own particular

existential and spiritual approach. For example, the image of

Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara symbolizes compassion as the central focus of the

spiritual experience; that of Manjushri takes wisdom as the central focus; and

that of Vajrapani emphasizes the need for courage and strength in the quest

for sacred knowledge.

2) Wrathful Deities: Wrathful deities suggest the mighty struggle

involved in overcoming one's alienation. They embody all the inner afflictions

which darken our thoughts, our words, and our deeds and which prohibit

attainment of the Buddhist goal of full enlightenment. Traditionally, wrathful

deities are understood to be aspects of benevolent principles, fearful only

to those who perceive them as alien forces. When recognized as aspects of

one's self and tamed by spiritual practice, they assume a purely benevolent guise.

2) Wrathful Deities: Wrathful deities suggest the mighty struggle

involved in overcoming one's alienation. They embody all the inner afflictions

which darken our thoughts, our words, and our deeds and which prohibit

attainment of the Buddhist goal of full enlightenment. Traditionally, wrathful

deities are understood to be aspects of benevolent principles, fearful only

to those who perceive them as alien forces. When recognized as aspects of

one's self and tamed by spiritual practice, they assume a purely benevolent guise.

3) Sexual Imagery: Sexual imagery suggests the integrative process

which lies at the heart of the mandala. Male and female elements are

nothing but symbols of the countless pairs of opposites (e.g. love and hate; good

and evil etc.) which one experiences in mundane existence. The initiate

seeks to curtail his or her alienation, by accepting and enjoying all things as a

seamless, interconnected field of experience. Sexual imagery can also be

understood as a metaphor for enlightenment, with its qualities of

satisfaction, bliss, unity and completion.

3) Sexual Imagery: Sexual imagery suggests the integrative process

which lies at the heart of the mandala. Male and female elements are

nothing but symbols of the countless pairs of opposites (e.g. love and hate; good

and evil etc.) which one experiences in mundane existence. The initiate

seeks to curtail his or her alienation, by accepting and enjoying all things as a

seamless, interconnected field of experience. Sexual imagery can also be

understood as a metaphor for enlightenment, with its qualities of

satisfaction, bliss, unity and completion.

COLOR SYMBOLISM OF THE MANDALA

If form is crucial to the mandala, so too is color. The quadrants of

the mandala-palace are typically divided into isosceles triangles of

color, including four of the following five: white, yellow, red, green and

dark blue. Each of these colors is associated with one of the five

transcendental Buddhas, further associated with the five delusions of human nature.

These delusions obscure our true nature, but through spiritual practice

they can be transformed into the wisdom of these five respective Buddhas.

Specifically:

White - Vairocana: The delusion of ignorance becomes the wisdom of

reality.

White - Vairocana: The delusion of ignorance becomes the wisdom of

reality.

Yellow - Ratnasambhava: The delusion of pride becomes the wisdom of

sameness.

Yellow - Ratnasambhava: The delusion of pride becomes the wisdom of

sameness.

Red - Amitabha: The delusion of attachment becomes the wisdom of

discernment.

Red - Amitabha: The delusion of attachment becomes the wisdom of

discernment.

Green - Amoghasiddhi: The delusion of jealousy becomes the wisdom of

accomplishment.

Green - Amoghasiddhi: The delusion of jealousy becomes the wisdom of

accomplishment.

Blue - Akshobhya: The delusion of anger becomes the mirror like

wisdom.

Blue - Akshobhya: The delusion of anger becomes the mirror like

wisdom.

THE MANDALA AS A SACRED OFFERING

In addition to decorating and sanctifying temples and homes, in

Tibetan life the mandala is traditionally offered to one's lama or guru when a

request has been made for teachings or an initiation - where the entire

offering of the universe (represented by the mandala) symbolizes the most

appropriate payment for the preciousness of the teachings. Once in a desolate

Indian landscape, the Mahasiddha Tilopa requested a mandala offering from his

disciple Naropa, and there being no readily available materials with which

to construct a mandala, Naropa urinated on the sand and formed an

offering of a wet-sand mandala. On another occasion Naropa used his blood,

head, and limbs to create a mandala offering for his guru, who was delighted

with these spontaneous offerings.

Conclusion

The visualization and concretization of the mandala concept is one of

the most significant contributions of Buddhism to religious psychology.

Mandalas are seen as sacred places which, by their very presence in the world,

remind a viewer of the immanence of sanctity in the universe and its

potential in himself. In the context of the Buddhist path the purpose of a mandala

is to put an end to human suffering, to attain enlightenment and to attain a

correct view of Reality. It is a means to discover divinity by the

realization that it resides within one's own self.

Nitin G.

From this Website

Posted with Nitin G.'s permission

Back to Apprentice Weavers

|